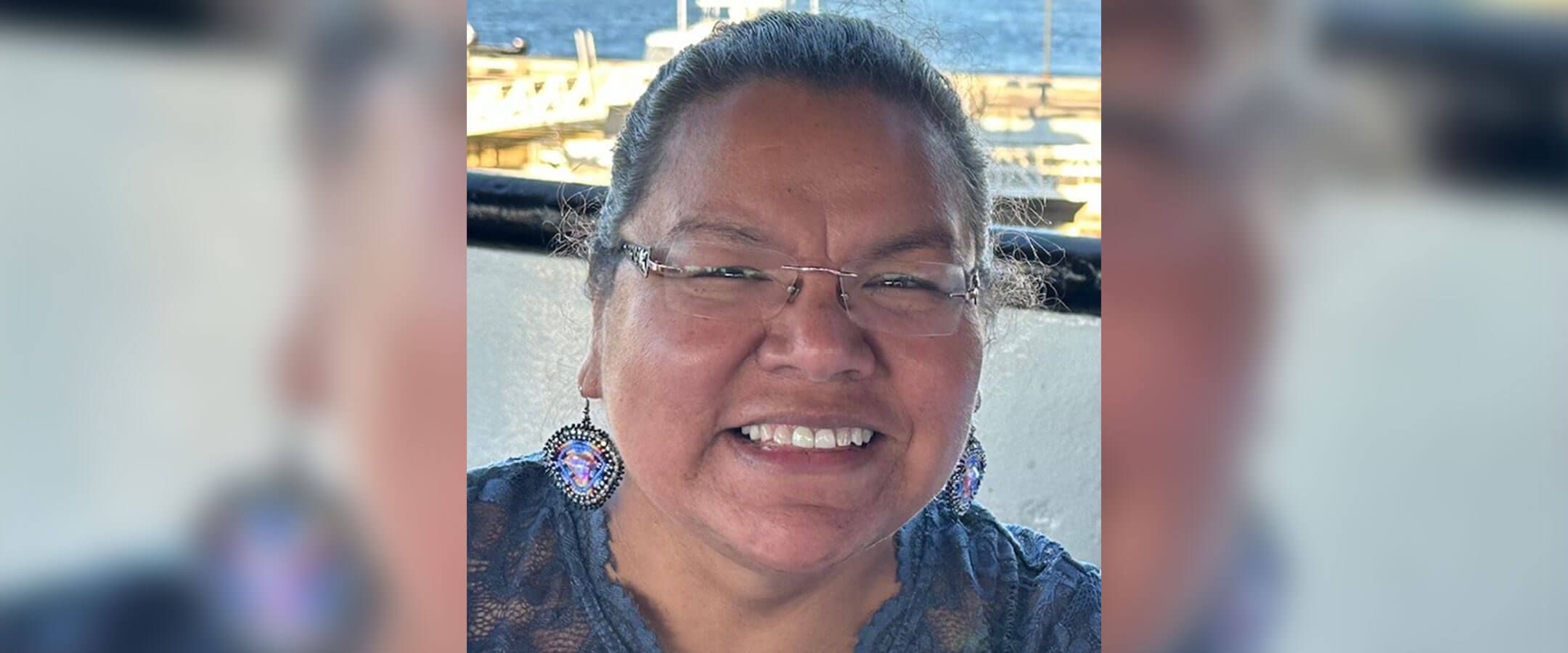

When Kiana Chang x’25 was considering future careers, she thought in terms of practicality: she wanted job security and financial stability. Fields like business and technology caught her eye. Eventually, she landed on a major in information systems, a field she says combines the best of business and the tech industry and explores how these skill sets can improve peoples’ lives. It was this tenet — the practical application of her skills to serve her community — that led Chang to conduct award-winning and personally rewarding work well before entering the postgrad job market.

Chang is the Hmong/HMoob farm outreach student assistant with the UW Division of Extension. (HMoob is an emerging term that is considered more inclusive of this population’s two main dialects. It also incorporates letters from all three terms used to describe their group identity: Hmong, Mong, and Hmoob.) As a member of this community herself, Chang took this opportunity to use her UW education to level the planting field.

For Hmong/HMoob people, growing food is a form of self-sustenance, a viable livelihood, and a way of preserving and celebrating culture. However, those practices become precarious as many such farmers in Wisconsin struggle with language and technology barriers that subject them to unfair land agreements and unequal access to agricultural resources.

“That’s why I’m doing this work,” Chang says. “I really, really want to give my community this opportunity that everyone else has.”

Chang creates resources and promotional materials for UW Extension workshops geared toward supporting Hmong/HMoob farmers in Wisconsin. She’s grown the Wisconsin Hmong/HMoob Farmers Facebook group from 21 to nearly 300 followers, facilitated farmer-to-farmer connections, created language for partner organizations to reach the Hmong/HMoob community, and developed linguistically accessible resources for crucial agricultural information like soil health and pest control. For her work, she received the UW’s 2023–24 Student Employee of the Year — Community Service award and was a runner-up for the same recognition from the Midwest Student Employee Association.

Here, Chang shares her journey from being a bored teen in her grandparents’ garden to helping people just like them — and their crops — thrive.

What attracted you to work in the agricultural sector?

In the description, they specifically listed that they were going to work with Hmong farmers. [That was] the first thing that made me think, “Oh, I’ve got to do this” — the fact that they’re even looking to help Hmong people. I’m Hmong, and not a lot of people know about Hmong people in general [and] the history of them. Growing up, I saw a lot of struggles for Hmong farmers, my grandparents included, and that’s a very big part of why I decided to take on this job. I [felt] like if I can take this on, I can have more of an impact for my own community, specifically, my grandparents. I could give them the resources that they never had before in terms of land access [and] market access.

Did your grandparents teach you about Hmong farming practices?

It’s not really “farming” [in which they] have cattle and whatnot. It’s more towards gardening: they have their own gardens and then sometimes they take us to their gardens. But being young, me and my siblings were like, “We don’t like this. This is not fun. I don’t know why we do this. This is not enjoyable.” But now, I appreciate a lot more looking back, like them taking us to the gardens and trying to teach us what they do and passing down agricultural practices. I’m still not that familiar with [it all], but that’s why I am working with Hmong farmers now and still learning.

A lot of the agricultural practices that the older generation has [are] hard to [pass] down because there aren’t many of the younger generation looking to do gardening and farming. In a way, we’re kind of losing those practices, but that’s why we’re trying to record those practices in videos and on paper.

What else does your work with Extension entail?

We’re doing a lot more videos because a lot of the older generation, it’s harder for them to get access to written materials. They don’t really know how to use social media like that. And if they do, it’s easier to watch a video. So, I, along with [UW Extension’s farm management outreach specialist] Gaonou Thao, have been working to make video content on land access, record-keeping, and the financial aspects and legal stuff.

A lot of Hmong farmers work with people who own a farm and then rent land. They can get basically scammed [if] it’s not on a legal, written document, so if a [landowner] was to pull out of that agreement and the Hmong farmer didn’t have a written document, [the farmer] can’t do anything about it. They would just lose all their produce. That’s why we’re trying to do a lot more videos on how to go through those legal steps to have proper security for [their produce and the land on which they grow it].

We’ve also been working with the [National Resources Conservation Service] because they have a lot of written material in Hmong already for agriculture practices, so we’ve been working with them to try to share it out more and to see if there’s any more content we can make in terms of written documents in Hmong.

It’s [also] a lot of translation work. Translation is so hard. But I’ve been doing some videos reaching out to professionals and specialists in agriculture [and] Hmong workers to try to give Hmong farmers insight into what kind of career paths they can go into in agriculture.

I also do a lot of promotional work because we have workshops. We had one recently on weeding tools [where we] displayed different weeding tools that we have, and then our Hmong farmers could come and check out all the different tools we have, and we would show them where you can buy it and how much it is.

What have you learned while working on this project?

I think it really helped me connect more with my community. Growing up, I had this inner conflict: I am with Hmong people, but I also don’t really like some of the things historically we do in terms of the patriarchal hierarchy, which really just made me dislike [and] push away my own culture. But I think this opportunity has really made me connect more with the older generation because I work with Hmong farmers and most of the Hmong farmers are a lot older. I get to talk to them, and I learn their struggles, and it helps me see more into how they think. It’s been helping me kind of come to terms [with] my cultural identity, as well.

Can you share any especially memorable moments from working on this project?

We had a tent set up at the Hmong Wausau Festival in 2023, and I got to talk with a lot of Hmong people who are interested in our group. I got to tell them what I do … and I was able to talk more to the younger kids and [ask], “Hey, do you have a grandma? Do you have a grandpa? Or do your mom and dad farm? Do you know if they use Facebook, and [if] they don’t, do you think you could share this with them? I think this would be really helpful for them.” And then they’re like, "Oh yeah, my grandparents farm. I think this is great for them.” Seeing how interested they were and trying to share these resources to their own grandparents reminded me of myself [and] how excited I was to start it because I wanted to share the potential resources we make with my own grandparents.