What accomplishments or stories are you most proud of working on throughout your career?

When I spoke at the university, I was the chief White House correspondent for CBS News, and I was covering the Clinton administration. So, that was interesting and exciting. I left to join Sunday Morning, one of our flagship broadcasts [at CBS News]. It is the number one rated morning program across the board. Even though it’s only on Sundays, their ratings are usually the highest of any morning show, so it’s exciting to be part of that. And I have covered politics, I have done international stories, I have done entertainment stories, lifestyle. I have done many stories on art, which is one of the really fun things that I love to do. Some stories that are on trends, some stories that are on legal subjects, because before I became White House correspondent, I was a longtime law correspondent for CBS.

So, all of those things have been part of what I’ve done over the years, and I’ve got, I think, it’s now 11 national Emmys, so that’s been good. Some of them are for group projects … about four or five of them may even be for Sunday Morning, which as an ensemble frequently wins the best news program of the year award. So that’s fun.

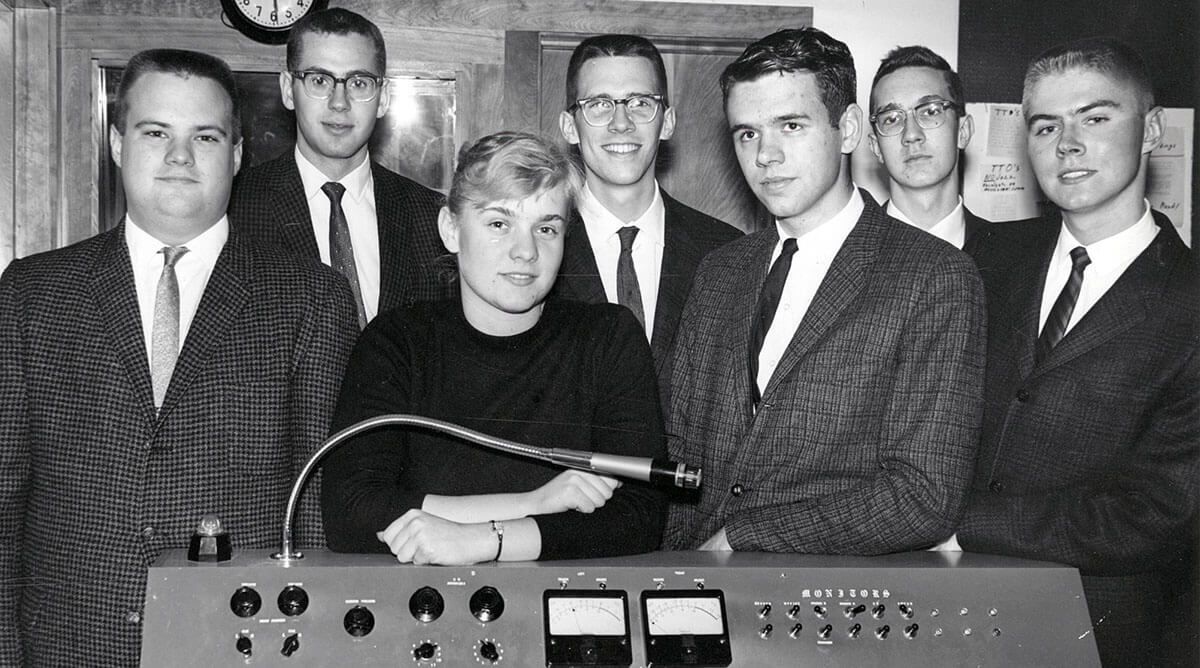

You have a political science degree from the UW — did you go into school knowing that’s what you wanted to pursue? Did you have a career in news media in mind at the time?

I was probably eight or nine when I knew that I wanted to be a journalist. So, I always had that in mind. I actually started thinking I was going to be a journalism student at UW, but when I was there, you had to take about half of your courses in advertising and business, in addition to the actual journalism — the writing and the reporting classes. I just knew that wasn’t a direction I wanted to go, and I felt like I didn’t want to spend my precious classes doing that. So, that’s when I switched to poli sci. In those days, you couldn’t really get credit on your diploma for a double major, but I did the English major as well. And I took a lot of art history, which has stood me in very good stead covering all the art stories I do now.

Can you remind the class of 1997 what you spoke about at commencement?

I wanted to give them something to remember, and what I like to tell kids about — I think having heroes is a really great thing. Having people that you look up to, that you admire, that you want to emulate is a very good thing. So, I spoke about another Wisconsin alum, who by then had passed away. Her name was Elizabeth Glaser.

She graduated a year or two ahead of me at Wisconsin. She was a good friend of mine. She had an unimaginable thing happen to her. … She was married to a well-known actor, Paul Glaser, at the time. He had been in a famous show called Starsky & Hutch. She had a daughter and a son, and her daughter started getting sick, and they couldn’t figure it out. It turned out that Elizabeth had had a very, very hard delivery. She had lost blood. She had gotten a blood transfusion. They knew there was some tainted blood, some AIDS-tainted blood in the hospital, but they insisted to her that she had not gotten that. They discovered that a little bit after the fact of her getting the transfusion. It turned out that she had, in fact, gotten the AIDS-tainted blood, and she didn’t know it, so she breast-fed her daughter.

Her daughter started getting sick and sick and sick. They finally asked if it was okay to test her for AIDS, of all things. And when the daughter turned out as positive for AIDS, they were trying to figure out how she could have tested positive. They said to Elizabeth, “Have you ever had a blood transfusion?” She told them about the transfusion. They discovered this tainted blood. And, of course, Elizabeth herself developed AIDS, and so did her young son.

She knew that her daughter was dying. She knew that she was going to die, but she was trying to save her son. So, she founded the Pediatric AIDS Foundation. It was very hard. She was doing it in secret because people discriminated so badly against people who had AIDS. Her husband was afraid that he wouldn’t get work.

[In Washington] … they weren’t doing any research on kids — on AIDS in children. It was all about what was going on in adults. And she got them to agree to try some of the drugs on children. Her child was very unusual. Most of the children being born to people with AIDS were the children of drug addicts or prostitutes, and it was very unusual, so they didn’t have advocates. She became that advocate.

[The Pediatric AIDS Foundation] first uncovered the fact that it would be possible to treat children. If the mother had AIDS, they could block the baby from getting AIDS. And so, her work has led to just remarkable research. That’s who I spoke about at the commencement. And her son is still living by the way. She succeeded in saving her son’s life.

What advice do you have for the class of 1997 now?

The advice I would have for them now is, and I might have even said this then, but I would really advise them not to forget to have fun. We all end up working so hard. We are so obsessed with doing our jobs and doing a really good job that we forget that life is supposed to be about enjoyment, as well as work. Jennifer Senior wrote a book, All Joy and No Fun. And I think that happens. You may take joy from your family, but you forget to have fun with them. So, don’t forget to have fun. Don’t forget.